Melia Belli Bose

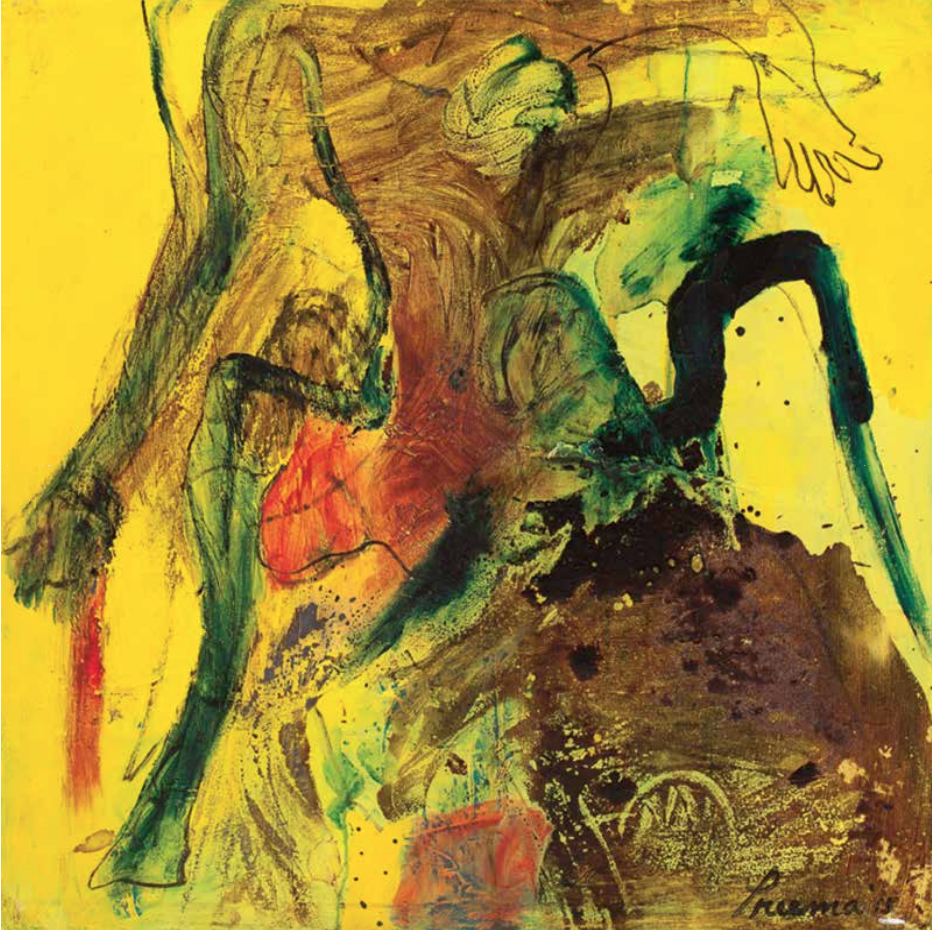

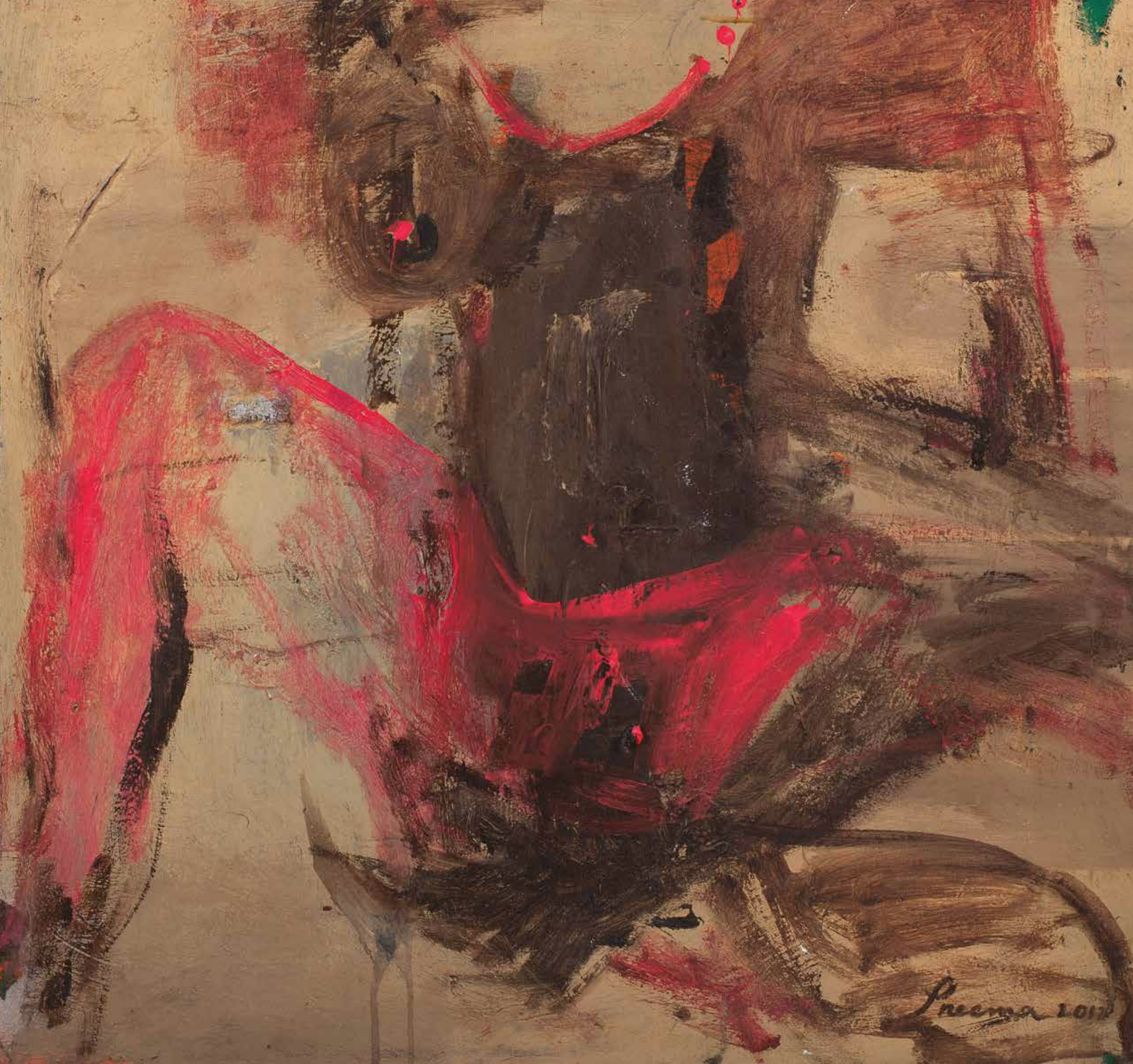

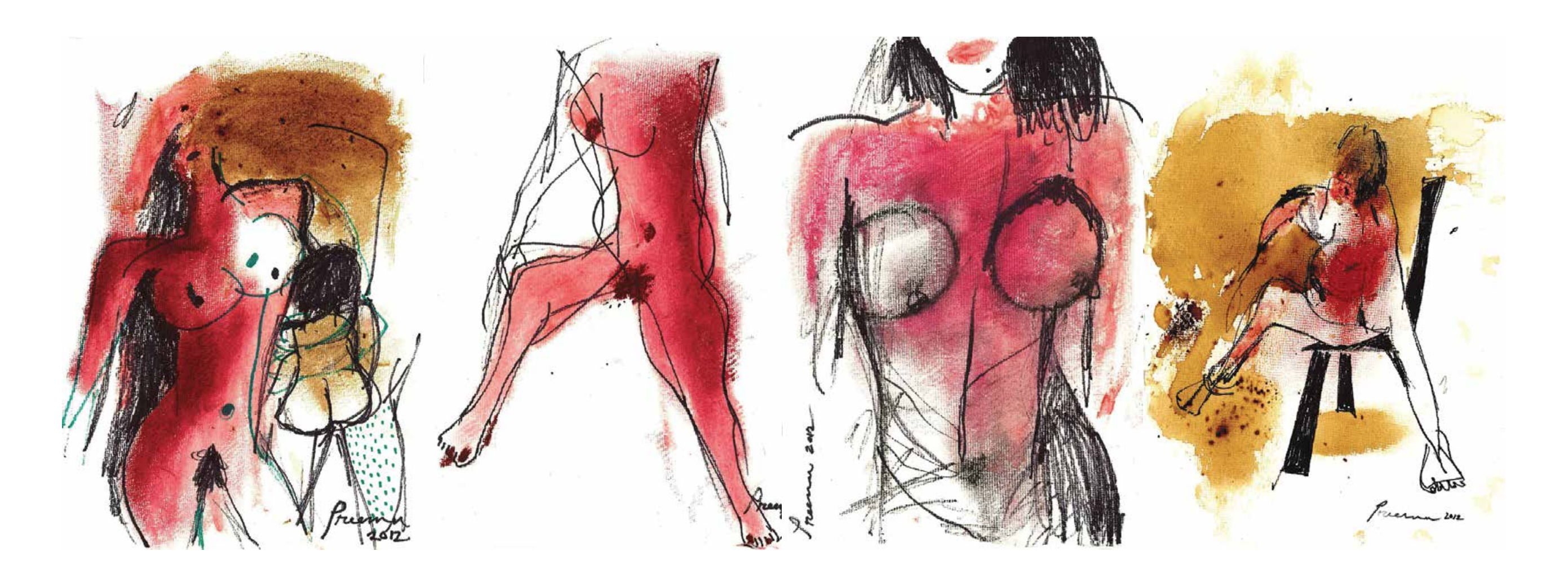

Throughout her nearly fifteen year career, women have been a perennial subject in the work of Bangladeshi artist Nazia Andaleeb Preema. In her often large-scale, vibrantly-hued, multi-media paintings, Preema explores aspects of women’s public and private lives, identities, and desires, as well as their bodies. Preema’s best known depictions of women feature in two ongoing series: Staring Women, begun in 2009, and Objectified, begun in 2012. Paintings from both are displayed in this exhibition. In these series the artist offers opposing manifestations of womanhood that challenge widely-held stereotypes of women’s agency and objectification both in Bangladesh and beyond. Echoing rising contemporary trends in her country of covering the female body, the artist depicts the women of Staring Women in hijabs and niqabs. However, rather than cast them as victims or as exotic, as in many renditions of veiled women, the paintings provoke questions of women’s identity and personhood. Conversely, in Objectified, Preema focuses on individual parts of the female anatomy, in response to what she perceives as a global tendency to reduce women to fetishized body parts, and the erosion of their individuality and agency.

Reversing the Gaze : Staring Women

Bangladesh is a new nation that is currently undergoing both rapid globalization and religious conservatism. One of the most visible impacts of the latter is the increasing popularity of veiling among women. This, Preema asserts, leads not only to women’s (literal) invisibility, but also to a broader social tendency to view them as passive, unexpressive, and subservient. Preema asks: “If women are not seen, how can they be heard?”

In the early 1970s, feminist art historian Linda Nochlin and film historian Laura Mulvey called attention to the fact that the visual arts are structured with a presumed masculine viewer. Globally, visual culture tends to depict the world and the female subject from a masculine point of view, and reaffirm inherent imbalances of power. Thus, until the later twentieth century, women were depicted in art primarily for the visual pleasure of the male gaze. Throughout South Asia, the gaze is also a gendered performance of power in everyday life. In much of South Asia the characteristics of shame and reserve (lojja in Bangla) are among the most favorable feminine traits. Manifestations of lojja include veiling and not meeting the gaze of an unknown male. In South Asia, men are not bound to such social conventions and thus enjoy more opportunities to gaze directly-at-women. Hence, in many South Asian socio-religious traditions, veiling is the most active way a woman can preserve her lojja. In Staring Women Preema examines confluences of lojja, agency, desire, and the feminine gaze. Paintings in the Staring Women series depict wide-eyed, veiled young women resolutely making eye contact with the viewer. The majority of the staring women reverse the gaze by brazenly peering out from their canvases and meeting the audience’s gaze. Perhaps more unsettling, other women in the series focus their gaze on a distant object of desire and dismiss their viewers. Preema frequently depicts the staring women’s eyes with a network of red veins, suggestive of a silent rage or profound longing. In so doing, the artist assigns greater complexity to her staring women. Rather than passively fading into invisibility, they delight in the empowered female gaze and express their individuality through desire.

In several paintings from the series, Preema complicates issues of women’s global objectification. In these works, she juxtaposes her painted veiled women with supermodels she cuts from the pages of fashion magazines, presenting them as if in a standoff, or clash of civilizations. However, as Western media, entertainment, consumer goods and depictions of women in Western clothing are now readily available in Bangladesh, these once sharply defined categories are becoming ever more porous and hybrid. Preema also hopes that Staring Women provokes her audience to reconsider issues of women’s agency and objectification, particularly with regard to their own body and self-expression. Ultimately, as the artist highlights, agency and objectification are not dictated by geography or a singular culture. She makes explicit through her depiction of these two extremes of womanhood: the veiled Muslim Bangladeshi woman and the impossibly slim, statuesque, surgicallyenhanced Western supermodel. These two examples highlight how women throughout the world are pressured to conform to culturally dictated gender norms.

Fetish and Scandal : Objectified

There is a long and well-established history of the female nude in Indian art. However, as historians of Indian art such as Tapati Guha-Thakurta have aptly noted, India’s relationship with the nude is nevertheless fraught and complex. While pre-modern depictions of nude female divinities enjoy widespread appreciation, more recent renditions of the subject, particularly in secular contexts, have been the subject of scandal and censorship. There is also precedent in modern Indian art of female artists rendering the nude. Rukmini Varma paints women from Indian mythology as nudes and Amrita Sher Gil painted living women, herself among them, in the nude. While their work was the subject of widespread criticism when it was first displayed – Varma in the 1970s, Sher Gil in the early twentieth century—their nudes are now among the most celebrated works of modern Indian art.

The female nude has enjoyed a similarly declining popularity in Bangladeshi art. While the numerous Pala and Sena Buddhist and Hindu sculptures featuring voluptuous female nudes are among Bangladesh’s national treasures, there is essentially no tradition of the nude in contemporary Bangladeshi art. One exception is the paintings of Shahabuddin Ahmed—the most commercially successful Bangladeshi artist in the country— in whose work nudes of both sexes often feature. Factors that may account for the perceived acceptability of the nude in Shahabuddin’s work is the fact that they are rendered with their genitals discreetly hidden, engaged in activity, and perhaps most important, they were painted by an older man.

When Preema displayed paintings of the female nude form her Objectified series in 2012-at-the Bengal Art Lounge, one of Dhaka’s premiere art venues, they were quickly removed due to public outcry. What was so scandalous about Preema’s nudes?

To understand why the artist’s paintings of nude women caused such a stir, something should be said about the manner in which the female body is depicted and the context in which they were executed. Each canvas in the Objectified series offers a delicate, pastel, earth, or jeweled-toned sketchily rendered and softly focused depiction of a part of a woman’s body: a leg that terminates in a pedicured foot, a breast, or the supine lover body with legs languidly parted to expose a vagina. Certainly, no other Bangladeshi artist had ever presented the female body in such a frank and straightforward manner before, and even Dhaka’s cosmopolitan, avant-garde gallery goers were shocked. Undoubtedly, many were also (unacceptably) titillated.

Then there is the story of the paintings’ origin, which Preema, who subscribes to notions of artistic freedom and candor, frankly shares with her audience. During a trip to Paris in 2012, the artist was marooned alone in her hotel room on a rainy day. She ordered a large pot of coffee, which together with the contents of her make-up bag, used as art supplies, producing a series of provocatively posed nudes, several of which later inspired oil paintings. Perhaps the scandal arose from the fact that Preema’s nudes are seductively posed, clearly welcoming the male gaze, and painted by a woman. Knowledge of the paintings’ origins—having been created by the artist when she was alone—also suggests that they are self-portraits, a subject about which the artist prefers to neither confirm upon, nor deny. The title of the series, however, is unambiguous—Preema takes control, objectifying and offering herself for visual consumption. In so doing she places herself on par with woman across the world who are reduced to fetishized body parts by the media, entertainment, and advertising industries, and the male gaze.

Viewed together, Staring Women and Objectified address the double bind Bangladesh women confront today. As Preema notes: “Showing a women’s body is a taboo in our society, but how can we not show that which has been objectified for so long!” Is a woman greater than the sum of her parts? One wonders how Amrita Sher Gil, who grappled with the various parts of her identity, sexuality, and background, might have answered this question.